That is the question.

I commonly get the question, “should I strengthen ______?” But I feel like I’ve heard it more than ever the last few weeks in the office and while out treating athletes at competitions.

Say you had been playing a bunch of Golf and couldn’t play in the Olympics this week because of a bum shoulder. Regardless of fantastical shattered dreams, you have a shoulder that can’t move well, feels weak and stiff, hurts during or after activity — it just sucks. If you didn’t have a traumatic injury such as walking off the edge of a cliff while playing Pokemon, where you obviously compromised the shoulder (if not more), then what’s the problem? Are the muscles weak? Do we need to strengthen the shoulder? Maybe. But 9 times out of 10 it’s not primarily a strength issue; however, don’t fret, the thought process is logical!

What’s the issue then?

“Strength” is a term used very loosely in the various physical medicine fields. If you have muscle atrophy for whatever reason and now you need to strengthen that muscle to get it back to normal size, then yeah, sure go ahead and strengthen it. However, this is not the common occurrence. If you have weakness due to significant structural impairment needing surgical or medical intervention, then strengthening is no good until that’s corrected. The most common presentation is a joint articulation imbalance likely due to the inability to adequately control the joint dynamically in a functional movement. What in tarnation does that mean!? Welp, I’ll try to make it as simple as possible because I could go on and on to ad nauseum. And I have no idea what “tarnation” actually means, but it does remind me of an old curmudgeon.

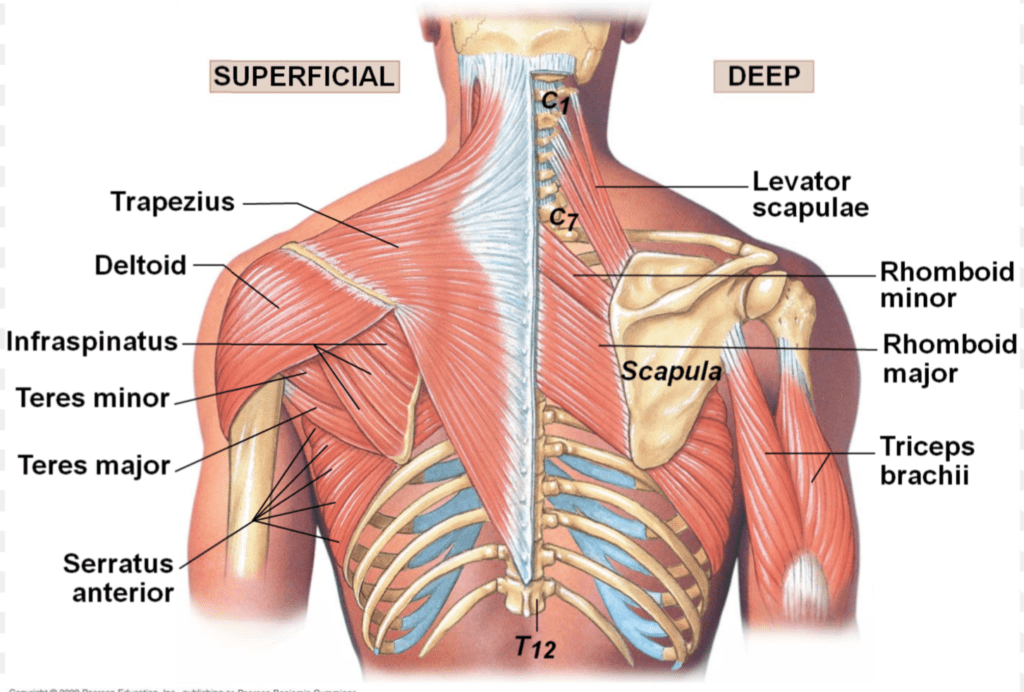

The shoulder’s only bone-on-bone connection to the rest of the body is through one measly joint where you collar bone meets your chest: sternoclavicular joint. Unlike the hip where we can use its hefty articulation for stability, the shoulder is primarily stabilized by muscles. Fun fact: 17 muscles attach directly to the shoulder blade — wowzers! If something is off whack (medical term), it changes the entire dynamic of the shoulder. It’s as if you went to a totally gnarly Wham! concert and George Michael performed, like, grody to the max — jitterbug would be soooo jitter-dud! Okay, terrible example but 80’s babies would (may) appreciate it. What I’m attempting to articulate (pun intended) is if even one muscle of a joint complex isn’t pulling its weight, it affects the entire joint negatively, just like a band in concert would suffer if one of its musicians wasn’t feeling during a performance. Just like that old adage, “you’re only as strong as your weakest link.”

Okay, keep going.

To continue the music analogy, if the muscles of the shoulder aren’t playing to together very well, what do you do? The typical approach is to strengthen the shoulder cuff muscles with various exercises utilizing stretchy bands and light weights.

The approach above is great early on in a rehab program when there’s true weakness or atrophy of a muscle(s), but it’s very limited regarding return to higher function. Why? Becuase with these movements you are isolating a few muscles out of many. Remember, 17 muscles attach to the shoulder blade alone, which does not include big hitters such as the pec and lat that do not attach to the shoulder blade but influence the kinematics shoulder immensely. This is like training the players of the string instruments, but ignoring the rhythm section, horn section, and other woodwind & percussion instruments. It doesn’t matter how good the fiddlers are when the trombone, xylophone and flugelhorn suck — again, you’re only as strong as your weakest link.

To continue the music theme even further, what about the rest of the body? You got it; they have to play nice as well. It doesn’t matter how strong your “cannon” is if you cannot stabilize and transfer forces efficiently. This is a topic of its own, but to smash a tennis ball, whip a baseball, or pound the white off a golf ball, you must generate ground reactive forces. The baseball pitcher utilizes the white rubber on the mound to drive energy from the ground, through the body, down the arm, finally to the release of the ball. To achieve this, the body has to stabilize and transfer forces. Try shooting a cannon out of canoe — not going very far. Is a more powerful cannon the answer? Throwers considered to have strong arms create and transfer ground reaction forces extremely well, not because their throwing arm can rep 100-pound dumb bell curls.

Examples, please.

Take a look at a few of the strongest arms in the NFL. Two are Superbowl winning QBs, but the Lions are winning it this year, amiright!? Sure, Tom Brady models for UGG boots but none of these guys are competing in strength or bodybuilding competitions anytime soon, yet they can throw a pigskin over a friggin’ mountain. Strongmen are the best at picking stuff up and putting it down, but you very rarely see that physique in throwing/swinging athletes.

Why can’t a massive human being smash through a stack of cement blocks while someone half the size can make it look like slicing butter? Why could Bruce Lee execute the famous 1-inch punch measuring in at 5′ 7″ and a buck forty-five? The ability to generate and transfer forces.

Okay, so what do I do about it?

Strengthen, duh. Seriously, though. I’m going to make a shameless plug for my movement colleagues and myself: See a therapist educated in human movement and biomechanics. They (and I) will be able to identify your weak link(s) and offer strategies that you can employ yourself. Ultimately, to become more efficient in your respective sport, reducing the risk of injury (there’s no such thing as prevent) and improve performance.

In the meantime:

Learn how to breathe abdominally.

- The ability to create intraabdominal pressure via diaphragmatic breathing is numero uno.

Do the common uncommonly well.

- No one likes fundamentals, but those that are experts at fundamentals typically have the edge. Be the best at the basics.

Execute movements slow and controlled.

- Anyone can power through an exercise by using cheat mechanisms — e.g., momentum, holding breath, curling toes, clenching teeth — but try to execute a movement slowly throughout every phase of the movement without the cheat mechanisms above. It’s pretty tough. Speed hides need, so if you slow it down, you get instant feedback of where you lack control — you’re weak links.

Don’t bring a mobility fix to a stability problem.

- If you have tight ______, the logical thought is to stretch it, roll it, mash it, mobilize it. This can definitely help in the short-term, but it’s likely a revolving door of stretch it, tight again. When this happens — quite often — there’s a reason why it’s tight in the first place. This is a topic of another conversation, but the short answer is tightness is your brain’s way of protecting a joint that doesn’t feel safe moving as far and in a particular direction you want it to. Tightness is safety mechanism; an attempt to prevent injury.

I hope you found this interesting and learned something today. Shoot me an email with any questions because I know you have them! Just because something’s mainstream doesn’t make it correct!

– Dr. RJ Burr