Save Time. Save Money. Get Peace of Mind: Skip the MRI

Save Time. Save Money. Get Peace of Mind: Skip the MRI

Even if you don’t follow golf, you may have heard that Tiger Woods has undergone his fourth back surgery in four years. You’d think if the problem was identified by MRI and considered correctable by surgical procedure it would have worked for him the first time. Or second. Even third. But no, he needs a fourth to get it right his time! Now, I’m no surgeon but maybe, just maybe, surgery is not going to solve the problem.

About a month ago, Rory McIlroy was having problems, too, and he considered imaging:

“I’m going for an MRI scan on Monday just to make sure it’s not serious, and then I’ll see what we do from there.”

Serious? Like tumor, fracture, or infection serious? Because that’s what you’re hoping to rule out when you refer someone for an MRI.

Wait, it’s just back pain that has unexpectedly persisted? Welcome to the club, but you don’t need an expensive picture for membership!

Here are four reasons why it’s best to skip the MRI:

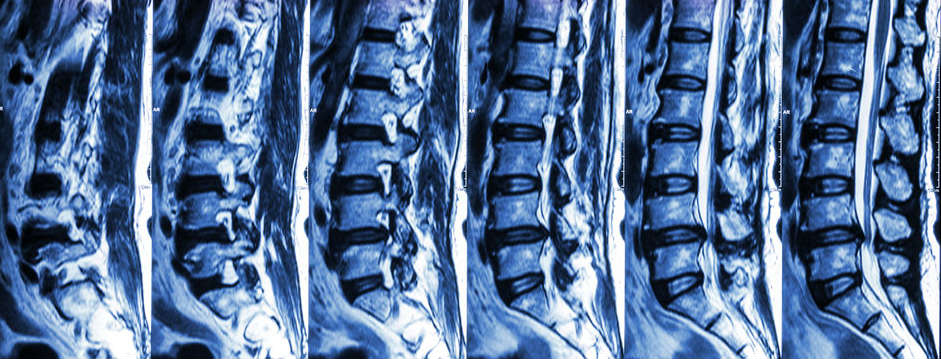

1. “Scary” findings likely have nothing to do with your pain

According to Rory’s age group, there’s a 30% chance he may have a disc bulge, and a 37% chance there’s disc degeneration; however, the study[1] that reported this data was from people WITHOUT pain. It may sound crazy, but even if they do find degeneration or bulge in Rory’s MRI, it likely has nothing to do with his current pain at all.

MRI’s are highly sensitive and poorly specific, meaning they’ll pick up on a lot of stuff, but whether that stuff has anything to do with your problem[2] is unlikely unless there are correlating clinical diagnostics and judgments to pose an argument.

Better yet, a study determined the consistency of MRI findings between multiple radiologists, and the results were astonishing. This study[3] found, “marked variability in the reported interpretive findings and high prevalence of interpretive errors in the radiologist’s reports of an MRI exam of the lumbar spine performed on the same patient at 10 different MRI centers over a short period.”

Not only are MRI findings correlative at best, professionals interpreting them have varying opinions of what’s what. And you want to get surgery based on this data? It’s no wonder we’re concluding common orthopedic surgeries are in many cases no better than placebo[4]!

The medical community is now realizing that correlative image findings are simply a part of the normal aging process. Just as when we age we get wrinkles on the outside, we get wrinkles on the inside.

2. It can mess with your head

Another major problem with a trigger-happy mentality to imaging is what it does to the patient’s psyche. It’s not uncommon for a patient to experience a reoccurrence and say, “Oh that’s my arthritis acting up.”

People will literally identify themselves with their X-ray or MRI image. It’s like AA but wildly unnecessary. “Hello, my name is ______ and I have a slipped disc.”

Why is this a problem? Carragee[5], all the way back in 2005, showed that there was little correlation between structural findings and low back pain, but psychosocial variables strongly predicted both short and long term disability.

This study[6] showed that catastrophizing after seeing your image and receiving the diagnosis is a common coping strategy but is associated with delayed recovery and poor treatment outcomes.

3. It’s expensive

It may sound ridiculous, but getting an MRI first can cost you more in the long-run, not just psychologically, but monetarily as well.

MRIs cost an average of $2600. With insurance, it may not be that bad but coverage is getting increasingly worse and worse, requiring more and more out of your own pocket.

MRI follow-ups typically lead to medications, injections, potential surgeries and so on. All of this costs a pretty penny.

A comparative study[7] in 2013 at a large U.S. manufacturing facility assessed 434 subjects under mechanical care and 4,602 who sought standard medical care. Mechanical care produced a 51.5% savings and reduced the utilization of MRIs, injections, and surgeries by an average of 67%!

But let’s not forget what else this could potentially cost you:

- The opioid epidemic has become a major problem in this country, which is partial to blame for the heroine epidemic.

- Surgery: risks associated with procedures, time lost away from work, there’s no guarantee it will change your pain.

- Long-term disability because all options were thought to be exhausted. The cause of the problem was never identified and solved.

A recent Consumer Reports article suggests drugs and surgery may not be the answer, either.

4. It doesn’t change the course of conservative treatment.

As a conservative musculoskeletal mechanical and movement therapist (chiropractor by professional title), I look at body mechanics: how well someone moves and how that influences their symptoms.

An MRI doesn’t tell me how the person in front of me moves their body, just like taking a picture of a door doesn’t tell me how well it opens and closes.

I’ve seen many patients with previous diagnoses from radiologic findings, even having undergone surgery without results, that completely resolve with conservative mechanical care.

Did I repair their rotator cuff, remove their bone spur, or regenerate their degeneration?

Hell no.

Then how on Earth did their problem resolve? The pain generator (the actual problem) triggered a pain signal in a remote location in relation to the actual problem. The imaging results were merely incidental, not the problem or pain generator.

You know how a heart attack can cause shoulder pain? A back problem causing pain down the leg (sciatica) is the same idea. However, those who treat the shoulder during a heart attack are asking for a malpractice lawsuit!

When a patient’s history and evaluation determines the problem is not of mechanical nature or they simply aren’t responding to treatment as expected, I’ll order and imaging study or make the necessary referral for a medical evaluation.

How it should work: Get a conservative biomechanical evaluation, then medical, if necessary; not the other way around as we are accustomed to in our “sick care” model.

To Conclude

Unless there are other major concerns in Rory’s medical and health history that would warrant further testing, all he’s going to do is create problems and confusion that could get to his head. (Like our boy, Tiger!)

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-MRI, but as clinicians, it’s more about how we come to conclusions rather than how long we have been coming to conclusions. What I mean is we need to rethink how we diagnose and treat patients with common musculoskeletal pain opposed to trusting a big, fancy machine dethroning our clinical judgment as king just because it gives us a look at what’s inside.

For patients, it means we need to educate ourselves, ask questions, and get other opinions.

For you, it means saving time, saving money and getting peace of mind – skip the MRI!

Need a second opinion? Not sure if you’re ready to visit a trusted professional? Schedule a courtesy call with a REACH Doc — we’ll lead you in the right direction, toward a solution!

RJ Burr, DC, Cert. MDT

Doctor of Chiropractic

References

[1] Brinkikji, Luetmer, Comstock, et al. “Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations” American Journal or Neuroradiology 36 (2015): 811-816. doi:10.3174/aknr.A4173.

[2] Englund, Guermazi, Gale, et al. “Incidental Meniscal Findings on Knee MRI in Middle-Aged and Elderly Persons” The New England Journal of Medicine 359 (2008): 1108-1115. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800777.

[3] Herzog, Elgort, Flanders. “Variability in diagnostic error rates of 10 MRI centers performing lumbar spine MRI examinations on the same patient within a 3-week period” The Spine Journal 17 (2017): 554-561. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.11.009.

[4] Schroder, Skare, Reikeras, et al. “Sham surgery versus labral repair or biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder: a three-armed randomised clinical trial” British Journal of Sports Medicine (2017). doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097098

[5] Caragee, Alamin, Miller, et al. “Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain” The Spine Journal 5 (2005): 24-35. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.250.

[6] Wertli, Eugster, Held, et al. “Catastrophizing-a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: a systematic review.” The Spine Journal 14 (2014): 2639-2657. doi:10.1016.j.spinee.2014.03.003.

[7] Donelson, Spratt, Gray, et al. “The cost impact of a precise mechanical diagnosis on low back pain care: a comparison with usual community care” Publish Pending.